Childhood is a period of immense growth, not just physically but also intellectually, emotionally, and socially. At this time, play emerges as a cornerstone – a fundamental driver of development. This paper examines the concept of play-based learning, exploring its theoretical underpinnings and practical applications in learning environments.

Unveiling the Essence of Play and its Impact on Learning

Play, at its heart, is an intrinsic human drive. It is a spontaneous and joyful exploration of the world, free from external constraints. Children engage in play for its inherent pleasure, not for predetermined outcomes. This intrinsic motivation fuels a powerful learning engine. Play, in its essence, is the spontaneous and joyful exploration of the world. Play-based learning, therefore, harnesses this natural inclination, utilizing play as a vehicle for education and development. At its core, it is about learning through engagement, discovery, and interaction.

Play-based learning is rich with theories, each offering unique insights into its significance in childhood development. Notable figures such as Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky, Friedrich Froebel,

Maria Montessori, and Susan Isaacs have all contributed seminal works on the subject.

Theoretical Frameworks:

Play-based learning draws upon a wide range of theories. Here, we explore the contributions of three key figures:

Jean Piaget and Constructivism: Piaget posited that children actively construct their understanding of the world through play. Activities like sorting blocks or building with Legos become laboratories for developing logical thinking, problem-solving skills, and spatial reasoning. Play allows children to manipulate objects, experiment, and refine their understanding of the world.

Working under a Piagetian approach, which has significantly influenced Developmentally Appropriate Practice, the perspective that children learn ‘naturally’ through play, with the teacher facilitating opportunities for play in the environment, is apparent.

Maria Montessori and Open-Ended Play: Montessori emphasized the importance of providing children with open-ended materials that stimulate their creativity and imagination. A simple block corner transforms into a magnificent castle or a futuristic spaceship, from the imagination of the child. This freedom to explore encourages independent learning and allows children to learn at their own pace.

Lev Vygotsky and How Play Drives Cognitive Development: Lev Vygotsky saw play as a critical element in a child’s development, particularly for cognitive growth. His work emphasizes that children experiment, take risks, and try things beyond their current abilities from their imagination. This allows for growth with guidance from adults or more skilled peers. He also believed play is inherently social. Children collaborate, negotiate roles, and communicate ideas during imaginative play.

This social interaction fuels learning and development as per Lev Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory. Play allows children to practice and develop language skills. They experiment with different vocabulary, sentence structures, and storytelling through make-believe scenarios. Overall, Vygotsky’s ideas suggest that play provides a rich environment for children to learn and develop cognitively, socially, and linguistically.

Beyond Theory: Applications in Learning Environments

Play-based learning translates into practical applications within classrooms and learning spaces:

Creating Playful Environments: Learning environments that embrace play offer dedicated spaces for exploration. Open areas for building and running around, a designated dress-up corner with costumes and props, and a rich selection of art supplies and educational toys all contribute to a stimulating and playful atmosphere.

Integrating Play into Curriculum: Activities can be designed to integrate play seamlessly into learning objectives. Storytelling and role-playing can enhance literacy skills, while collaborative games can introduce concepts of fairness, cooperation, and strategy. This integration ensures that play is a purposeful and enriching part of the learning journey.

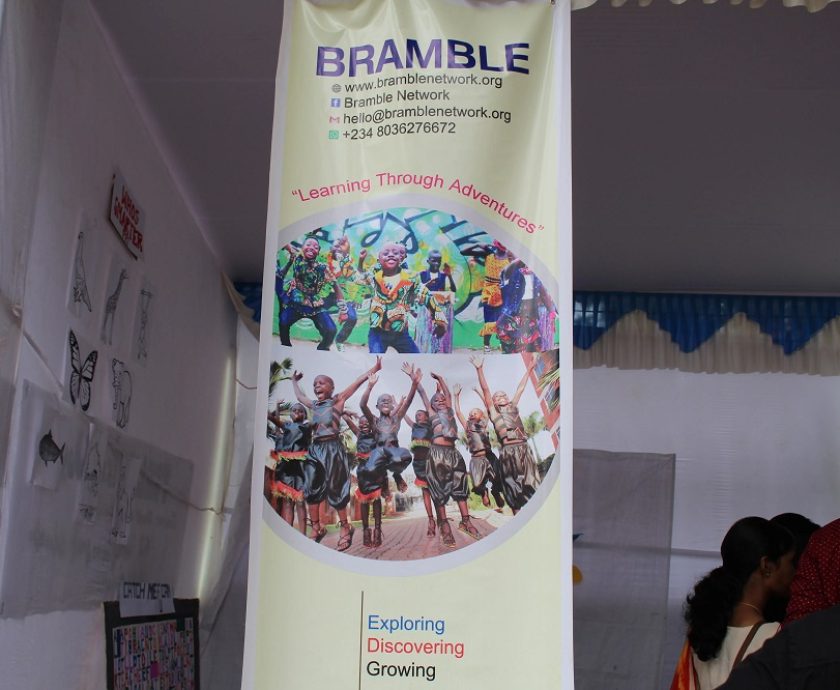

Play at the Core of Alternative Education Methodologies: Bramble Network as a non-profit organisation utilises play-based learning strategies to deliver education in rural communities.

We have through these strategies ignited a love for long-life learning in young people from rural and marginalised communities. By integrating play into the curriculum, Bramble Network encourages a more engaging and learner-centered approach that addresses the unique needs and challenges faced by learners from rural communities. We have myriads of examples of transformed learners. From children with learning disabilities to girls who thought education was never for them because of cultural biases. Having impacted over 300 learners across several communities, Bramble Network is at the forefront of incorporating play into education.

The Benefits of Playful Learning:

The benefits of play-based learning extend far beyond mere entertainment. It fosters development across multiple domains:

Cognitive Development: Play stimulates logical thinking, problem-solving skills, and memory. Building with blocks, sorting objects, and engaging in imaginative play all contribute to cognitive growth.

Social Development: Play provides a platform for developing social skills like communication, collaboration, and empathy. Children learn to share, take turns, and navigate group dynamics through play.

Emotional Development: Play allows children to express emotions, manage stress, and develop a sense of self-confidence. Pretend play and games provide opportunities to explore several emotions and develop coping mechanisms.

Physical Development: Active play is crucial for healthy physical development. Running, jumping, and building with blocks all contribute to motor skills development and coordination.

Conclusion:

According to LEGO’s “Play Well Study 2024,” On average, three in five children would like to play more than they do now, while four in five children would like to play more with their parents or caregivers. The research also shows that eight in ten children say adults don’t always think playing is important and seven in ten don’t believe adults take play — and how it can help them learn — seriously.

Play is a fundamental right; it builds resilience, instils confidence and helps children develop. But children need time to play. That’s where we need policies, training and funding to get play integrated into education and community settings.

Play heals through learning, life skills and psychosocial well-being. That’s why there must be investment into diverse, inclusive and safe play spaces, extending access to all, especially the most vulnerable and marginalized children. There are so many reasons we should all be celebrating the power of play.

Play-based learning is not just about fun and games; it is about harnessing a child’s natural desire to explore and learn. By deconstructing the essence of play and exploring the theoretical frameworks surrounding it, we can create learning environments that foster cognitive, social, emotional, and physical development. This International Day of Play, let’s celebrate the power of play and its undeniable role in shaping a child’s future.

References

Books

Piaget, J. (1951). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood. W. W. Norton & Company.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1930, 1933, 1935)

Montessori, M. (1967). The absorbent mind. Montessori-Pierson Publishing Company. (Original work published 1912)

Froebel, F. (1887). The education of man. Translated by Hailmann, W. N. Appleton. (Original work published 1826)

Isaacs, S. (1952). Intellectual growth in young children. Routledge.

Reports

The LEGO Group (2024). Play Well Study 2024.

Articles

Walsh, G., McGuinness, C., & Sproule, L. (2017). ‘It’s teaching … but not as we know it’: using participatory learning theories to resolve the dilemma of teaching in play-based practice. Early Child Development and Care, 189(7), 1162–1173. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1369977